Withdrawal symptoms from antidepressants are rarer than thought – Health

She had not expected this when, at the age of 50 and in “excellent physical condition,” as she reports, she was prescribed paroxetine to combat stress at work. She was already suspicious when the first side effects appeared: sexual dysfunction, emotional numbness, and then, at some point, a lack of motivation. But the doctors should know what they are doing, the psychiatrists at the University of California? Framer’s most important insight after her long odyssey from doctor to doctor, from medication to medication: They didn’t know.

First of all: Adele Framer’s story is an extreme and rare case. It does not justify giving up antidepressants, which help many people. But it does dramatically demonstrate that antidepressants are not gentle happy pills that you should just try when you’re feeling bad. They are medications, they often have unpleasant side effects, and they regularly cause problems when you stop taking them.

Adele Framer has made a significant contribution to the spread of this insight in clinical practice, at least in the English-speaking world. Above all, thanks to the website SurvivingAntidepressants.org, which she founded, where sufferers can exchange information and seek advice. An article published this week in the journal LancetPsychiatry A meta-analysis published by a research team led by Christopher Baethge from the University of Cologne and Jonathan Henssler from the Charité Berlin now draws the first comprehensive scientific conclusion. It is based on data from 20,000 people from 79 studies.

According to the study, around 31 percent of all patients suffer at least temporarily from health problems when they stop taking antidepressants. This is less than many experts would have expected, especially since 17 percent of the study participants also showed symptoms when taking a placebo. Experts are therefore also discussing methodological questions. What is particularly annoying is that such figures are only now available. After all, antidepressants are among the most prescribed and best-researched drugs in Germany, too, and have been on the market for decades. Early reports of problems when stopping treatment were already made in the 1960s. The first solid overview is a study by a working group led by Stanford psychiatrist Alan Schatzfeld in Journal of Clinical Psychiatry from 1997, which already lists all the typical symptoms. “It’s actually old news,” says Alkomiet Hasan, chief physician of the psychiatric clinic at the University of Augsburg, who regularly offers training on the subject at specialist conferences. “But it is still far too little known in medical care.”

Many doctors wanted to avoid antidepressants appearing like addictive substances

“People just didn’t want to believe it,” says psychiatrist Tom Bschor, co-author of the new Lancet-Study and currently head of the Government Commission for Hospitals at the Federal Ministry of Health. Many doctors wanted to avoid at all costs the suspicion that antidepressants could be addictive, as some critics of psychiatry still assume. Many psychiatrists still avoid the term withdrawal symptoms and prefer to talk about discontinuation symptoms.

All serious experts, both supporters and skeptics, agree that antidepressants are not addictive. According to the WHO definition, addiction only occurs when those affected can no longer control their consumption and have to increase it to achieve the same effect, when consumption leads to other interests in life being neglected and harmful consequences being ignored. None of this is the case with antidepressants. However, the withdrawal symptoms are similar to those seen with addictive sleeping pills or benzodiazepines.

“I don’t really care which word you use,” says Tom Bschor, shrugging his shoulders. In practice, it is much more important to differentiate between a relapse of the disease, which regularly occurs after stopping antidepressants. In fact, common withdrawal symptoms are similar to those of depression, such as tiredness, loss of appetite, depressed mood and much more. Doctors such as the Augsburg psychiatrist Alkomiet Hasan therefore recommend sticking to the FINISH rule, which is widely used in the professional world and which lists the most common withdrawal symptoms in an English-language mnemonic. These are flu-like symptoms, sleep disorders (insomnia), nausea, imbalance, sensory disturbances and irritability, agitation and anxiety (hyperarousal).

Almost more important in distinguishing between withdrawal symptoms and relapse is the temporal dimension, says Hasan: “Problems when stopping antidepressants almost always occur quickly within the first week, usually with a peak after 36 to 96 hours.” Depression, on the other hand, usually only returns after weeks.

It’s not just about the right term. If there is a relapse, a flare-up of depression, the doctor will usually prescribe medication again. A patient could therefore unnecessarily take antidepressants for a long time, sometimes years, which often have unpleasant side effects. In the case of pure withdrawal symptoms, however, it is usually sufficient to simply endure them or treat them symptomatically, if possible with medical supervision.

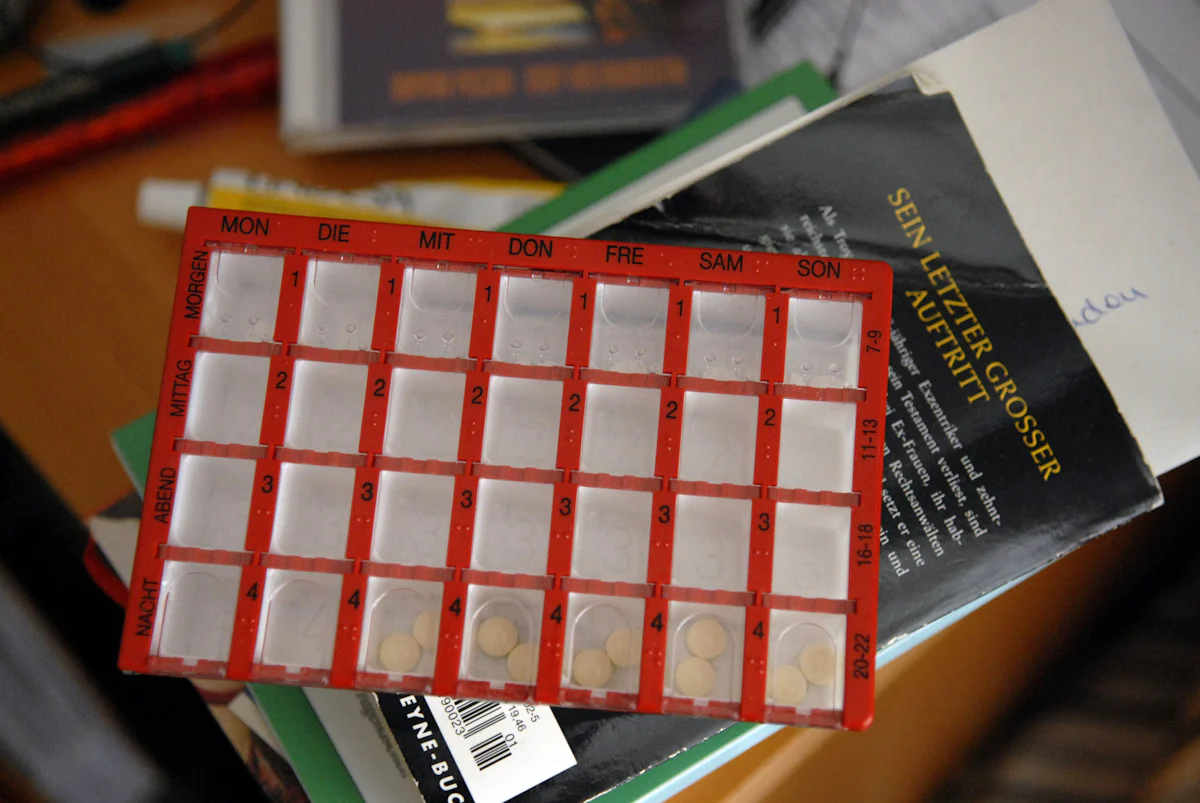

“A typical problem is patients who simply stop their treatment when they have used up their medication and the medication is no longer available,” warns Hasan. Withdrawal symptoms can be reduced or completely avoided if the medication is gradually tapered off over weeks or months, although the duration depends mainly on the active ingredient in question; these differ in how quickly the human body breaks them down. The length of time over which the antidepressant was taken, however, does not play a major role. Withdrawal can become problematic if a medication has been taken for more than one or two months; after that, the risk does not increase any further.

“These reports must be taken seriously, even if they are difficult to explain scientifically.”

The phase at the very end of the tapering process is particularly critical, as the body’s chemistry means that even the smallest dose changes have a strong effect. Those who follow the doctor’s advice will usually have no or only mild problems – and these usually disappear after two to six weeks, depending on the medication. If everything goes well.

It can also turn out differently. In rare cases, as Adele Framer painfully experienced, severe withdrawal symptoms occur. The new Lancet study estimates their share at 2.8 percent. Tom Bschor also knows of such cases from his clinical experience: people who have suicidal thoughts after stopping, become aggressive, and suffer from sexual disorders. “These reports must be taken seriously, even if they are difficult to explain scientifically,” says Bschor. Such symptoms are difficult to assess because they are very unspecific and very varied. “Perhaps those affected are just looking for an explanation,” says Bschor.

He believes that another danger is greater: the so-called rebound phenomenon, which he illustrates with the image of a ball that is pushed underwater: if you suddenly let go of it, it will bounce high above the water’s surface. In the same way, depression can return stronger than before after stopping medication, “quickly, particularly severely, difficult to treat,” says Bschor.

:Can antidepressants disrupt sexuality in the long term?

No more desire or impaired sensation in the genitals: patients complain about persistent sexual side effects of psychotropic drugs. What experts say.

Unfortunately, no one knows how often this phenomenon occurs. There are no reliable figures from studies, which is a regrettable gap in research. The experts’ assessments differ. As head of the psychiatric department at the Schlossparkklinik in Berlin, he used to see one to three such patients per week on the ward, with a total of 20 to 30 admissions, says Bschor. “It’s a significant problem, it worries me.” Alkomiet Hasan is a little more relaxed: “It’s not such a big problem.”

Nevertheless, both can agree that conclusions should be drawn from the findings on the withdrawal problem. General practitioners and psychiatrists should better educate their patients and follow the medical guidelines, according to which antidepressants are indispensable for severe depression, but should be prescribed as sparingly as possible for mild to moderate depression. In such cases, their effect remains manageable anyway.

“The worse alternative would be to prescribe addictive sleeping pills or benzodiazepines instead,” warns Hasan. And, of course, not everyone can find a psychotherapy place quickly. Bschor therefore recommends the “low-threshold cardinal measures” as doctors call them: sleeping only in the dark, doing chores, doing a positive activity during the day, sport and exercise. Otherwise, he is hopeful for the future: “We simply need better medication to treat depression.”

Ethel Purdy – Medical Blogger & Pharmacist

Bridging the world of wellness and science, Ethel Purdy is a professional voice in healthcare with a passion for sharing knowledge. At 36, she stands at the confluence of medical expertise and the written word, holding a pharmacy degree acquired under the rigorous education systems of Germany and Estonia.

Her pursuit of medicine was fueled by a desire to understand the intricacies of human health and to contribute to the community’s understanding of it. Transitioning seamlessly into the realm of blogging, Ethel has found a platform to demystify complex medical concepts for the everyday reader.

Ethel’s commitment to the world of medicine extends beyond her professional life into a personal commitment to health and wellness. Her hobbies reflect this dedication, often involving research on the latest medical advances, participating in wellness communities, and exploring the vast and varied dimensions of health.

Join Ethel as she distills her pharmaceutical knowledge into accessible wisdom, fostering an environment where science meets lifestyle and everyone is invited to learn. Whether you’re looking for insights into the latest health trends or trustworthy medical advice, Ethel’s blog is your gateway to the nexus of healthcare and daily living.