Helping hands from overseas: How 13 young Brazilians were recruited for nursing in Saxony

What does “Nu nu” mean? Yes, no, I don’t care? At first, Beatriz de Almeida Marques had a hard time understanding these regional subtleties. Learning German is already difficult enough for a young Brazilian. Just this “R” for emergency services…

Until last year, the 27-year-old only knew Germany from books and the Internet. “When I saw the advert, my heart started pounding,” she remembers. “I knew right away that I wanted to do this.” A job 8,000 kilometres from her home seemed to be exactly the right thing for her. An institution called the Dresden Heart Centre in Eastern Germany was looking for nursing staff – and she was already one, and an unemployed one at that.

What seems unthinkable in Germany today is still possible in Brazil: too many skilled workers in nursing professions. That’s why no one had to feel guilty when a delegation from Saxony set off for South America last year to cast 20 nurses in Brazil and recruit them for the heart center of the Dresden University Hospital.

Thanks to his German roots, 25-year-old Fritz Anthony had a head start in learning the language.

© SZ/Veit Hengst

In Saxony alone, there is currently a shortage of thousands of skilled nursing staff, and the situation will become even worse in the coming years. The heart center in Dresden has 220 hospital beds. Of the 763 employees working here, more than 500 are in nursing. Around one in ten are not from Germany. The casting project in Brazil was sponsored by the Free State of Saxony. The Central Agency for Foreign and Specialist Recruitment (ZAV) of the Federal Employment Agency (BA) offered to initially spread the appeal in South America.

In 2022, both countries had agreed to recruit 700 Brazilian nurses annually. In the meantime, the political wind has changed again. Brazil’s President Lula da Silva would rather keep his well-trained young people in his own country. Recruitment by the BA has therefore been suspended for the time being. The heart center was still able to use the network, while the Elblandkliniken, for example, have already canceled a similar project.

The number of applications for the heart center exceeded all expectations. Around 500 women and men could imagine embarking on the adventure. The prerequisite for taking part in the application process was a completed nursing degree. This takes five years in Brazil and has a good reputation.

The biggest challenge: How can the candidates learn German so well within a short period of time that they can communicate with patients in Dresden? First, however, a pre-selection had to be made from the 500 applications in Portuguese. Around 100 were translated into German and ultimately 40 applicants were invited for an interview. In September 2022, the Dresden residents boarded a plane and traveled to Recife, a port city with 1.6 million inhabitants in northeastern Brazil.

The new nurses are only allowed to administer medication after they have passed their exams.

© SZ/Veit Hengst

Uta Junghanns, deputy nursing director at the heart center, was also there. She was surprised when she was asked whether she could imagine flying to Brazil to recruit staff there. But she didn’t have to think about it for long. She knew that this wasn’t about sightseeing. She and the other members of the delegation had a marathon ahead of them in Brazil. Eight conversations with an interpreter every day for a week, each lasting around an hour.

After a final consultation, 20 applicants were chosen and given contracts on the spot. A kind of scholarship with free intensive language courses and 500 euros pocket money per month. It was important not to lose any time or promising candidates. The necessary printer for the contracts was also available.

While almost all candidates had to wait a while for the decision, one was accepted straight after the interview. At the same time, Fritz Anthony Gomes da Silva, then 24 years old, was the only one who already spoke some German. He comes from Paraiba, the easternmost tip of South America. His grandfather, who was also called Fritz and whom he never met, was from Germany. In 1942 he moved to Brazil. What Fritz Anthony’s mother never managed to do in her life – to visit her father’s old homeland – is now possible for her grandson.

The women and men chosen for the 20 positions immediately quit their jobs – if they had them – and were then asked to concentrate fully on their language courses. A challenge that not everyone was up to. As it turned out, some of those chosen lacked the necessary motivation over time. In the end, only one achieved the targeted B2 level, while twelve others at least managed to get to B1. These 13 were allowed to fly to Germany in October 2023. Seven stayed behind and dropped out of the project.

Shortly before the final exam: Anna feels ready for her future work at the Dresden Heart Center.

© SZ/Veit Hengst

In Dresden, the Brazilian nursing staff were faced with fully equipped one-room apartments near the heart center, a dirty autumn and the first snow of their lives in winter.

Simply arriving and starting work on the ward was not conceivable, despite the high level of qualification and, in some cases, years of practical experience. The requirements and training in the two countries are too different. At first, the 13 commuted to Chemnitz every day to continue learning German and a lot of theory about nursing work in Germany at the Eckert schools there. Then the so-called deficit notices came into play, which sound more negative than they are and only express the areas in which the young people have not yet been able to gain any experience.

In recent months, they have been trained for the fields of orthopedics, palliative medicine and geriatrics at the hospital in Freiberg, which, like the heart center in Dresden, belongs to Sana Kliniken AG, the third largest private hospital group in Germany. On the other hand, they learned internal medicine and cardiology directly at the Dresden heart center, their future place of work.

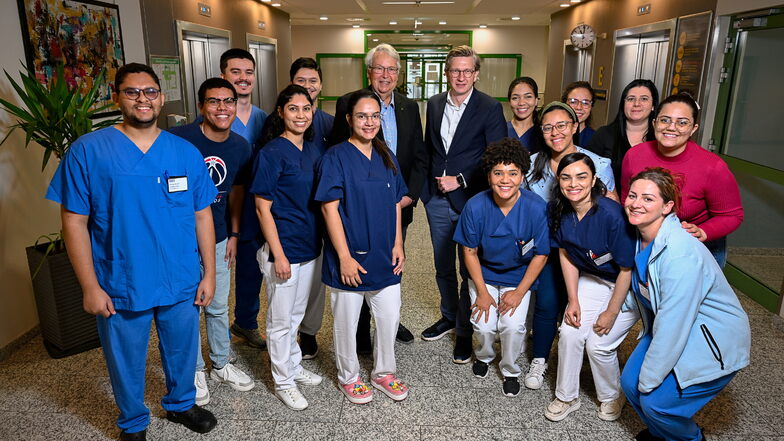

And here they are now: the Brazilian “gap fillers” who have long been much more than that for the hospital and the country, as clinic director Oliver Wehner and Saxony’s foreign affairs representative Geert Mackenroth both agree. The two welcomed the 13 Brazilians to Dresden two weeks ago at a ceremony in the lecture hall of the heart center. Two young Kosovars have now joined the group, which is working towards the final recognition test in November.

Saxony’s Commissioner for Foreigners Geert Mackenroth (centre back) visited the new nursing staff at the heart center in June.

© SZ/Veit Hengst

“The shortage of skilled workers is one of the major challenges we are currently facing,” says Mackenroth. There is currently a shortage of 4,000 nursing staff in Saxony and this need will continue to rise until at least 2030. Mackenroth therefore speaks of a “win-win situation for everyone” in relation to the project. “The fact that you are here today is not a given. This required a lot of travel, discussions and a great deal of confidence.” For the future, he hopes that this pioneering project will become a model for numerous other Saxon institutions, despite the now more difficult conditions.

The Brazilian nursing staff are helping Saxony to progress not only through their work, but also through their personality. “With their attitude to work, which is so exemplary that many Germans could learn a thing or two from it, their cheerfulness and their enriching nature.”

Before the group can grab some mini burgers decorated with German flags, Mackenroth advises the new arrivals to make sure they take the sunshine vitamin D. Oliver Wehner, meanwhile, feels it is important to stress that the focus in future should not only be on the newly recruited specialists. “Without the support of our old hands, such a success would not be possible,” he stresses. They are the ones who keep the system running in the “engine room of the hospital” with their commitment and reliability.

Clinical supervisor Anke Schubert-Hubrich has been with the company for 26 years.

© SZ/Veit Hengst

A mentoring system was designed especially for the Brazil project, which provides experienced staff to assist each Brazilian on the ward around the clock until the exam. Experienced staff like Anke Schubert-Hubrich, nurse, practice supervisor and has been with the hospital for 26 years.

The woman with the highly contagious positive aura and the wit that initially comes as a surprise in a hospital immediately hugs Beatriz to welcome her to ward 1A. Then she grabs Fritz Anthony and the young woman with the beautiful name Anna Karannyne Da Silva Queiroz de Albuquerque and takes the three of them to the injection room. Here the clinical instructor demonstrates how to prepare a Lasix injection, a standard medication at the heart center that helps rid the body of excess water.

The three nurses listen with interest and nod knowingly when Anke Schubert-Hubrich mentions the 6R rule: right patient, right medicine, right dosage, right form of administration, right time and right medical prescription.

Meanwhile, in the nurses’ station, the heart rates of all patients are beeping quietly on the monitors. On the wall next to it hangs a board in green, yellow and red, which indicates who is allowed to do what alone or at all for all tasks in the nursing service. Almost everything is marked in yellow for employees in recognition. They are therefore allowed to take on tasks such as facial care for ventilated patients, changing positions and calculating calories together with experienced specialists. Only a few activities, such as administering medication, are taboo for them.

In the syringe room, the candidates are trained for daily work on the ward.

© SZ/Veit Hengst

Beatriz is now preparing an ECG for a young patient. The stickers are quickly in the right places. “Please don’t move,” she says, still a little shy, and smiles. Shortly afterwards, the machine pushes out a long sheet of paper. The heart is fine. The patient can be discharged today.

The Brazilian nursing staff have brought a one-year work visa with them to Germany and will receive a longer residence permit after passing the test in November. Fritz Anthony will be able to apply for German citizenship in three years at the earliest, after the idea of naturalization through descent failed due to bureaucratic hurdles.

The 25-year-old already has very concrete plans for his future. “I want to stay in Germany until I retire,” he says. “And then I will move back to Brazil.”

But first he has to get used to Dresden and always answer the same three questions to the patients in the heart center: Why is a Brazilian traveling to Germany to work here? How do you like it here? And of course: Why is a Brazilian called Fritz?

Ethel Purdy – Medical Blogger & Pharmacist

Bridging the world of wellness and science, Ethel Purdy is a professional voice in healthcare with a passion for sharing knowledge. At 36, she stands at the confluence of medical expertise and the written word, holding a pharmacy degree acquired under the rigorous education systems of Germany and Estonia.

Her pursuit of medicine was fueled by a desire to understand the intricacies of human health and to contribute to the community’s understanding of it. Transitioning seamlessly into the realm of blogging, Ethel has found a platform to demystify complex medical concepts for the everyday reader.

Ethel’s commitment to the world of medicine extends beyond her professional life into a personal commitment to health and wellness. Her hobbies reflect this dedication, often involving research on the latest medical advances, participating in wellness communities, and exploring the vast and varied dimensions of health.

Join Ethel as she distills her pharmaceutical knowledge into accessible wisdom, fostering an environment where science meets lifestyle and everyone is invited to learn. Whether you’re looking for insights into the latest health trends or trustworthy medical advice, Ethel’s blog is your gateway to the nexus of healthcare and daily living.