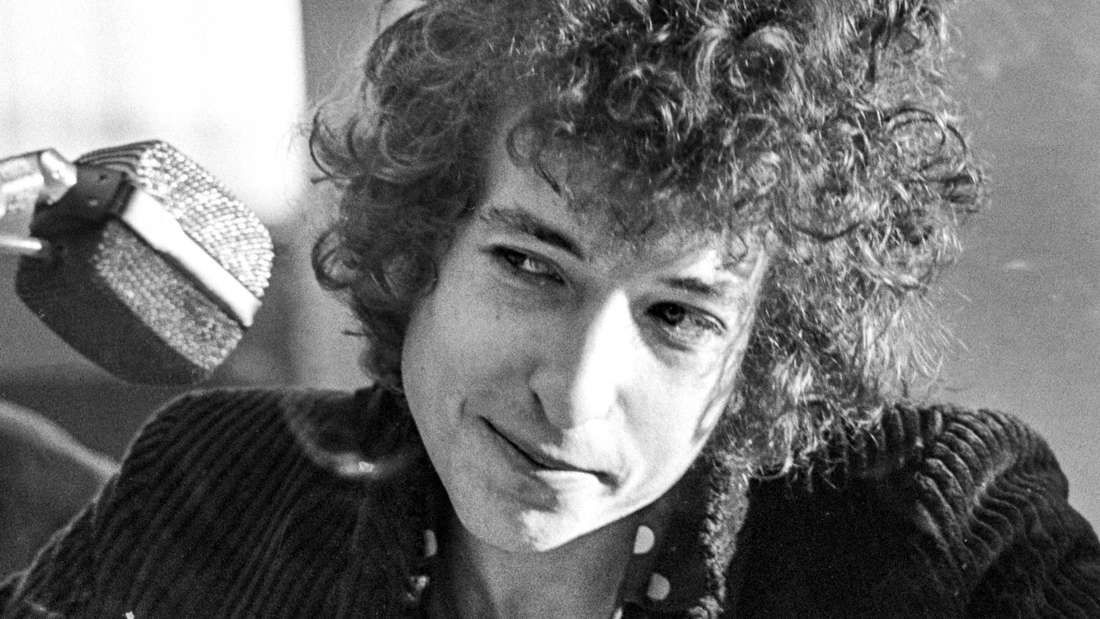

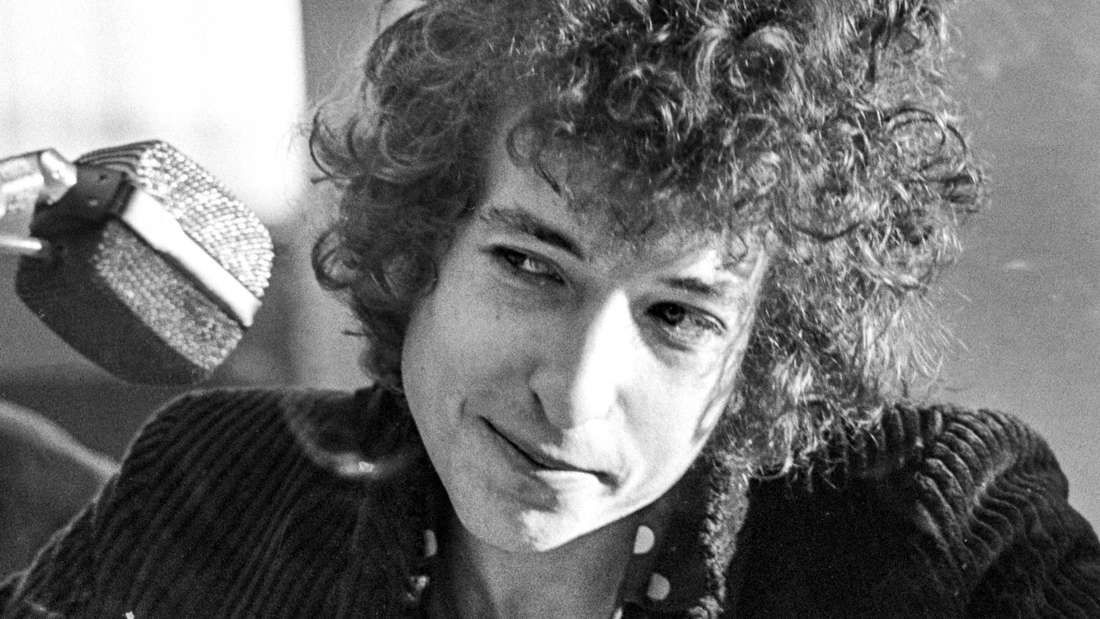

The Book “Mixing Up The Medicine”: Hanging Out With Bob Dylan

Press

The opulent volume “Mixing Up The Medicine” provides access to the almost inexhaustible archive of the musician and Nobel Prize winner

Bob Dylan traced the way the “tambourine man” came into his poetic universe back to the studio musician Bruce Langhorn. He had already played guitar on several of Dylan’s albums before producer Tom Wilson asked him to play the tambourine on one of his tracks. Pop mythology, the story behind the songs. Even if it may have happened completely differently, people like to tell and hear such things. The artist and his associations, a never-ending story.

Bob Dylan’s life and work are not exactly short of legends, and it is undoubtedly the result of an opulent marketing strategy that more and more Dylan media is being thrown into the ring. The community of those who cannot get enough of Dylan and his creations is as large as it is wealthy. In the regular bootleg series, of which number 18 from the late 70s has just been released, there are several CDs on which individual songs are presented in various variations, stylistic nuances and tempos as well as different instrumentation in the form of a special experimental arrangement. The interested listener is literally drawn into an imaginary studio and witnesses the creative process at the moment of its creation, including interruptions. Bob Dylan did this early on. On the album “Bringin’ It All Back Home” from 1965, he starts “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream” at the wrong tempo, starts laughing and, after a short conversation with Tom Wilson, starts again. Since then, the scene has become a classic for the unvarnished depiction of a recording process, a kind of indication of transparency, authenticity right here and now.

Bringing It All Back Home also includes “Mr. Tambourine Man,” which had been part of Dylan’s song repertoire for a while at the time, but had been on hold for inclusion on a studio LP. Really? More useless knowledge from the Dylan world about when and how it became what many believe it to be – a kind of neverending making-of?

The remarkable thing about the material and devotional objects, which are crammed with hundreds of pictures, posters, record covers, newspaper clippings, notes and much more, which, far beyond Bob Dylan, form a breviary of American popular culture from the late 1940s to the present day, is the desire to be drawn to details that are as superfluous as they are astonishing, and which one can hardly escape. The example of Bruce Langhorn and his tambourine is supported by the picture of the tambourine, a rhythm instrument the size of a wagon wheel, complete with a finely crafted and barely worn leather case. The tambourine itself seems to have suffered more. Despite or perhaps because of a few scratches, it shines in a greasy, dirty patina, and a piece has been torn off the edge of the animal hide. It was actually a Turkish frame drum, called a daf, with a diameter of 40 centimeters. Langhorn had bought it at Izzy Young’s Folk Center in Greenwich Village. The indelible association with the “Tambourine Man” was reflected in one of Dylan’s most beautiful and enigmatic songs, which early on contributed to the assumption that the nasal folk musician must have been a poet.

Dispersal, that is the idea

Anyone who starts talking about a 600-page book that offers deep insights into the Dylan archives of the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma, will not be able to avoid the suspicion that they are getting carried away. That is precisely the idea behind this product for nerds and insiders. Many of the legends skewered in the volume are merely warmed up and accompanied by contemporary references, such as the brief connection between Dylan and the French singer Françoise Hardy, which Dylan had previously sparked with a poem written especially for her.

The book

M. Davidson, P. Fishel (eds.): Bob Dylan: Mixing Up The Medicine. Translated from English by Pieke Biermann et al. Droemer 2023. 606 pp., 98 euros.

Unfortunately, a lot of things remain superficial, and often a kind of second look is missing, such as the one that actress Anne Wiazemsky, Jean-Luc Godard’s wife, later provided in her autobiography of the film “Sympathy For The Devil”, in which she tells, without vanity or a need for hero worship, about the genesis of the film documentary about the famous song by the Rolling Stones.

Unlike the recently published photographs by Paul McCartney from 1964, which provide an unobstructed view of the Beatles at a time when the Beatles had no idea who they would become as a band, the photos published in “Mixing Up The Medicine” show a musician who, from the very beginning, attached great importance to his appearance and its impact. Don McLean is probably right: the coat that Dylan had casually draped over his shoulders was from James Dean, whose films Robert Allen Zimmerman had seen as a teenager in Hibbing, Minnesota. Over the decades, Bob Dylan could also be described as a fashion-conscious and informed person who set many trends – from the Thunderclap model by the Baron Hat company in Burbank, which Dylan wore during the concerts of the Rolling Thunder tour in 1975, to the sunglasses by Bausch and Lomb, which bear a strong resemblance to the later iconic Wayfarer model by Ray Ban.

The volume consists of endless digressions and marginal notes, and it is about Dylan’s friendships. Some of them are part of pop history, such as his friendship with George Harrison of the Beatles. Less well known is his connection with the critic Paul Williams, which is even documented in letters from Dylan, who is self-confessedly lazy when it comes to writing.

It is a largely affirmative description, in addition to which boxes full of “odds and ends” are thrown at Bob Dylan. Despite a few photos showing him whispering intimately with James Baldwin, it is particularly striking in the recently published collection “The Philosophy of Modern Song” how marginal the work of black musicians is.

“Mixing Up The Medicine” is aptly described in a line by the writer Michael Ondaatje, who has contributed a short essay: “And it carries within it this significant artistic streak of lottering, of hanging around – a quality that we also find in Kurt Schwitters’s magnificent collages and Robert Frank’s photos.”

Ondaatje’s praise of “lottering” ultimately leads to an ode and variation on Dylan’s song about the black blues musician Willie McTell. “Actually,” says Ondaatje, “‘Blind Willie McTell’ should – as my friend, the poet DC Wright always thought – be the American national anthem.”

Ethel Purdy – Medical Blogger & Pharmacist

Bridging the world of wellness and science, Ethel Purdy is a professional voice in healthcare with a passion for sharing knowledge. At 36, she stands at the confluence of medical expertise and the written word, holding a pharmacy degree acquired under the rigorous education systems of Germany and Estonia.

Her pursuit of medicine was fueled by a desire to understand the intricacies of human health and to contribute to the community’s understanding of it. Transitioning seamlessly into the realm of blogging, Ethel has found a platform to demystify complex medical concepts for the everyday reader.

Ethel’s commitment to the world of medicine extends beyond her professional life into a personal commitment to health and wellness. Her hobbies reflect this dedication, often involving research on the latest medical advances, participating in wellness communities, and exploring the vast and varied dimensions of health.

Join Ethel as she distills her pharmaceutical knowledge into accessible wisdom, fostering an environment where science meets lifestyle and everyone is invited to learn. Whether you’re looking for insights into the latest health trends or trustworthy medical advice, Ethel’s blog is your gateway to the nexus of healthcare and daily living.